Historically, many rulers have assumed titles such as son of god, son of a god or son of Heaven. Roman Emperor Augustus referred to his relation to his deified adoptive father, Julius Caesar, as "son of a god" via the term divi filius which was later also used by Domitian.

"Son of God" is a title of Jesus in the New Testament of the Bible. In the New Testament, "Son of God" is applied to Jesus on many occasions. It is often seen as referring to his divinity, from the Annunciation through his birth, crucifixion, resurrection and beyond. In the New Testament, Jesus is declared to be the Son of God on two separate occasions by a voice speaking from Heaven. Jesus is also explicitly and implicitly described as the Son of God by himself and by various individuals who appear in the New Testament.

God the Son (Greek: Θεός ὁ υἱός) is the second person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies Jesus as God the Son,united in essence but distinct in person with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit (the first and third Persons of the Trinity). In Trinitarian Christian denominations "Son of God" refers not only to the personhood of Jesus within the Trinity, but also to the identical divine nature by which he is seen as God and spoken of as God the Son. Nontrinitarian Christians accept the application to Jesus of the term "Son of God", which is found in the New Testament, but not the term "God the Son", which is not found there.

Rulers and Imperial titles[edit]

Main articles: Divi filius, Imperial cult, Imperial cult (ancient Rome), and Sacred king

Throughout history, emperors and rulers ranging from the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC) in China to Alexander the Great (c. 360 BC) to the Emperor of Japan (c. 600 AD) have assumed titles that reflect a filial relationship with deities.

The title "Son of Heaven" i.e. 天子 (from 天 meaning sky/heaven/god and 子 meaning child) was first used in the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 B.C.). It is mentioned in the Shijing book of songs, and reflected the Zhou belief that as Son of Heaven (and as its delegate) the Emperor of China was responsible for the well being of the whole world by the Mandate of Heaven. This title may also be translated as "son of God" given that the word Ten or Tien in Chinese may either mean sky or god. The Emperor of Japan was also called the Son of Heaven (天子 tenshi) starting in the early 7th century.

Examples of kings being considered the son of god are found throughout the Ancient Near East. Egypt in particular developed a long lasting tradition. Egyptian pharaohs are known to have been referred to as the son of a particular god and their begetting in some cases is even given in sexually explicit detail. Egyptian pharaohs did not have full parity with their divine fathers but rather were subordinate. Nevertheless, in the first four dynasties, the pharaoh was considered to be the embodiment of a god. Thus, Egypt was ruled by direct theocracy, wherein "God himself is recognized as the head" of the state. During the later Amarna Period, Akhenaten reduced the Pharaoh's role to one of coregent, where the Pharaoh and God ruled as father and son. Akhenaten also took on the role of the priest of god, eliminating representation on his behalf by others. Later still, the closest Egypt came to the Jewish variant of theocracy was during the reign of Herihor. He took on the role of ruler not as a god but rather as a high-priest and king.

Jewish kings are also known to have been referred to as "son of the LORD". The Jewish variant of theocracy can be thought of as a representative theocracy where the king is viewed as God’s surrogate on earth. Jewish kings thus, had less of a direct connection to god than pharaohs. Unlike pharaohs, Jewish kings rarely acted as priests, nor were prayers addressed directly to them. Rather, prayers concerning the king are addressed directly to god. The Jewish philosopher Philo is known to have likened God to a supreme king, rather than likening Jewish kings to gods.

Based on the bible, several kings of Damascus took the title son of Hadad. The son of Panammuwa II a king of Sam'al referred to himself as a son of Rakib. The king Bar-Rakib is known from a stela bearing his inscription. Rakib-El is a god who appears in Phoenician and Aramaic inscriptions.

In Greek mythology, Heracles (son of Zeus) and many other figures were considered to be sons of gods through union with mortal women. From around 360 BC onwards Alexander the Great may have implied he was a demigod by using the title "Son of Ammon–Zeus".

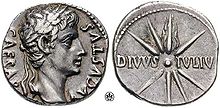

In 42 BC, Julius Caesar was formally deified as "the divine Julius" (divus Iulius) after his assassination. His adopted son, Octavian (better known as Augustus, a title given to him 15 years later, in 27 BC) thus became known as divi Iuli filius (son of the divine Julius) or simply divi filius (son of the god). As a daring and unprecedented move, Augustus used this title to advance his political position in the Second Triumvirate, finally overcoming all rivals for power within the Roman state.

The word applied to Julius Caesar as deified was divus, not the distinct word deus. Thus Augustus called himself Divi filius, and not Dei filius. The line between been god and god-like was at times less than clear to the population at large, and Augustus seems to have been aware of the necessity of keeping the ambiguity. As a purely semantic mechanism, and to maintain ambiguity, the court of Augustus sustained the concept that any worship given to an emperor was paid to the "position of emperor" rather than the person of the emperor. However, the subtle semantic distinction was lost outside Rome, where Augustus began to be worshiped as a deity. The inscription DF thus came to be used for Augustus, at times unclear which meaning was intended. The assumption of the title Divi filius by Augustus meshed with a larger campaign by him to exercise the power of his image. Official portraits of Augustus made even towards the end of his life continued to portray him as a handsome youth, implying that miraculously, he never aged. Given that few people had ever seen the emperor, these images sent a distinct message.

Later, Tiberius (emperor from 14–37 AD) came to be accepted as the son of divus Augustus and Hadrian as the son of divus Trajan. By the end of the 1st century, the emperor Domitian was being called dominus et deus (i.e. master and god).

Outside the Roman Empire, the 2nd century Kushan King Kanishka I used the title devaputra meaning "son of God".

Jewish literature

Although references to "sons of God", "son of God" and "son of the LORD" are occasionally found in Jewish literature, they never refer to physical descent from God. The phrases "son of God" or "son of the LORD" are never used in the Tanakh rather the LORD speaks to the king, telling the king that he is his son. The more correct usage in all of these passages is "son of the LORD". In addition there are two instances where Jewish kings are figuratively referred to as a god. The king is likened to the supreme king God. These terms are often used in the general sense in which the Jewish people were referred to as "children of the LORD your God". When used by the rabbis, the term referred to Israel or to human beings in general, and not as a reference to the Jewish mashiach. In Judaism the term mashiach has a broader meaning and usage and can refer to a wide range of people and objects, not necessarily related to the Jewish eschaton.

Genesis

Main articles: Nephilim and Sons of God

In the introduction to the Genesis flood narrative, Genesis 6:2 refers to "sons of God" who married the daughters of men and is used in a polytheistic context to refer to angels.

Exodus

In the Book of Exodus Israel as a people is called "God's son", using the singular form.

Psalms

Main article: Psalms

In Psalm 89:27-28 David calls God his father. God in turn tells David that he will make David his first-born and highest king of the earth.

Royal Psalm

Main articles: Royal Psalms , Melchizedek , and Priesthood of Melchizedek

See also: Jesus and messianic prophecy #Psalm 110 and Jesus and messianic prophecy #Psalm 2

Psalm 2 is thought to be an enthronement text. The rebel nations and the uses of an iron rod are Assyrian motifs. The begetting of the king is an Egyptian one. Israel’s kings are referred to as the son of the LORD. They are reborn or adopted on the day of their enthroning as the "son of the LORD".

Some scholars think that Psalm 110 is an alternative enthronement text. Psalm 110:1 distinguishes the king from the LORD although in later centuries this would become a source of confusion. Psalm 110:3 may or may not have a reference to the begetting of kings. The exact translation of 110:3 is uncertain. In the traditional Hebrew translations his youth is renewed like the morning dew. In some alternative translations the king is begotten by God like the morning dew or by the morning dew. One possible translation of 110:4 is that the king is told that he is a priest like Melchizedek. Another possibility is to translate Melchizedek not as a name but rather as a title “Righteous King”. If a reference is made to Melchizedek this could be linked to pre-Israelite Canaanite belief. The invitation to sit at the right hand of the deity and the king’s enemy’s being used as footstools are both classic Egyptian motifs, as is the association of the king with the rising sun. Many scholars now think that that Israelite beliefs evolved from Canaanite beliefs. Jews have traditionally believed that Psalm 110 applied only to King David. Being the first Davidic king, he had certain priest-like responsibilities.

Psalm 45 is thought to be a royal wedding text. Psalm 45:7-8 may refer to the king as a god anointed by God, reflecting the king’s special relationship with God.

Some believe that these psalms where not meant to apply to a single king, but rather where used during the enthronement ceremony. The fact that the Royal Psalms were preserved suggests that the influence of Egyptian and other near eastern cultures on pre-exile religion needs to be taken seriously. Ancient Egyptians used similar language to describe pharaohs. Assyrian and Canaanite influences among others are also noted.

Samuel

In the 2 Samuel 7 David is referred to by the LORD as my son. The LORD makes a promise to David and his line. The promise is one of eternal kingship.

Isaiah

Main article: Pele-joez-el-gibbor-abi-ad-sar-shalom

See also: Jesus and messianic prophecy #Isaiah 9:5 (9:5,6)

In Isaiah 9:6 the next king is greeted, similarly to the passages in Psalms. Like Psalm 45:7-8 he is figuratively likened to the supreme king God Isaiah could also be interpreted as the birth of a royal child, Psalm 2 never the less leaves the accession scenario as an attractive possibility. The king in 9:6 is thought to have been Hezekiah by Jews and various academic scholars.

Book of Wisdom

The Book of Wisdom refers to a righteous man as the son of God.

Dead Sea Scrolls

In some versions of Deuteronomy the Dead Sea Scrolls refer to the sons of God rather than the sons of Israel, probably in reference to angels. The Septuagint reads similarly.

In another Dead Sea fragment (which is only partially complete) a son of God is mentioned. The exact meaning is unclear.

In 11Q13 Melchizedek is referred to as god the divine judge. Melchizedek in the bible was the king of Salem. At least some in the Qumran community seemed to think that at the end of days Melchizedek would reign as their king.

Pseudepigrapha[edit]

In both Joseph and Aseneth and the related text The Story of Asenath, Joseph is referred to as the son of God. In the Prayer of Joseph both Jacob and the angel are referred to as angels and the sons of God.

Talmud

This style of naming is also used for some rabbis in the Talmud.

Christianity

See also: God the Son, Jesus in Christianity, Divine filiation, and Adoptionism

|

The terms "sons of God" and "son of God" appear frequently in Jewish literature, and leaders of the people, kings and princes were called "sons of God".

Psalm 2:7 reads

I will tell of the decree of the Lord: He said to me, "You are my son; today I have begotten you. Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your possession. You shall break them with a rod of iron, and dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel."

Psalm 2 can obviously be seen as referring to a particular king of Judah, but has also been understood of the awaited Messiah.

In the New Testament, the title "Son of God" is applied to Jesus on many occasions. It is often used to refer to his divinity, from the beginning of the New Testament narrative when in Luke 1:32-35 the angel Gabriel announces: "the power of the Most High shall overshadow thee: wherefore also the holy thing which is begotten shall be called the Son of God."

The declaration that Jesus is the Son of God is echoed by many sources in the New Testament. On two separate occasions the declarations are by God the Father, when during the Baptism of Jesus and then during the Transfiguration as a voice from Heaven. On several occasions the disciples call Jesus the Son of God and even the Jews scornfully remind Jesus during his crucifixion of his claim to be the Son of God."

Of all the Christological titles used in the New Testament, Son of God has had one of the most lasting impacts in Christian history and has become part of the profession of faith by many Christians. In the mainstream Trinitarian context the title implies the full divinity of Jesus as part of the Holy Trinity of Father, Son and the Spirit.

However, the concept of God as the father of Jesus, and Jesus as the exclusive divine Son of God is distinct from the concept of God as the Creator and father of all people, as indicated in the Apostle's Creed. The profession begins with expressing belief in the "Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth" and then immediately, but separately, in "Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord", thus expressing both senses of fatherhood within the Creed.

Meaning

In the Old Testament no individual ever addressed God as "my Father". What Jesus did with the language of divine sonship was first of all to apply it individually (to himself) and to fill it with a meaning that lifted "Son of God" beyond the level of his being merely a human being made like Adam in the image of God, his being perfectly sensitive to the Holy Spirit (Luke 4:1, 14, 18), his bringing God's peace (Luke 2:14; Luke 10:5–6) albeit in his own way (Matt 10:34, Luke 12:51), or even his being God's designated Messiah.

Synoptic Gospels

According to the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus referred to himself obliquely as "the Son" and even more significantly spoke of God as "my Father" (Matt. 11:27 par.; 16:17; Luke 22:29). He not only spoke like "the Son" but also acted like "the Son" in knowing and revealing the truth about God, in changing the divine law, in forgiving sins, in being the one through whom others could become children of God, and in acting with total obedience as the agent for God's final kingdom. This clarifies the charge of blasphemy brought against him at the end (Mark 14:64 par.); he had given the impression of claiming to stand on a par with God. Jesus came across as expressing a unique filial consciousness and as laying claim to a unique filial relationship with the God whom he addressed as "Abba".

Even if historically he never called himself "the only" Son of God (cf. John 1:14, 18; John 3:16, 18), Jesus presented himself as Son and not just as one who was the divinely appointed Messiah(and therefore "son" of God). He made himself out to be more than only someone chosen and anointed as divine representative to fulfil an eschatological role in and for the kingdom. Implicitly, Jesus claimed an essential, "ontological" relationship of sonship towards God which provided the grounds for his functions as revealer, lawgiver, forgiver of sins, and agent of the final kingdom. Those functions (his "doing") depended on his ontological relationship as Son of God (his "being"). Jesus invited his hearers to accept God as a loving, merciful Father. He worked towards mediating to them a new relationship with God, even to the point that they too could use "Abba" when addressing God in prayer. Yet, Jesus' consistent distinction between "my" Father and "your" Father showed that he was not inviting the disciples to share with him an identical relationship of sonship. He was apparently conscious of a qualitative distinction between his sonship and their sonship which was derived from and depended on his. His way of being son was different from theirs.

Paul

See also: Pre-existence of Christ

In their own way, John and Paul maintained this distinction. Paul expressed their new relationship with God as taking place through an "adoption" (Gal. 4:5;Rom. 8:15), which makes them "children of God" (Rom. 8:16–17) or, alternatively, "sons of God" (Rom. 8:14; (Rom. 4:6–7). John distinguished between the only Son of God (John 1:14, 18; John 3:16, 18) and all those who through faith can become "children of God" (John 1:12; 11:52; and 1 John 3:1–2,101 John 5:2). Paul and John likewise maintained and developed the correlative of all this, Jesus' stress on the fatherhood of God. Over 100 times John's Gospel names God as "Father". Paul's typical greeting to his correspondents runs as follows: "Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the/our Lord Jesus Christ" (Rom 1:7; 1 Cor 1:3; 2 Cor 1:2; Gal 1:3; Phil 1:2; 2 Thess 1:2; Philem 3). The greeting names Jesus as "Lord", but the context of "God our Father" implies his sonship.

Paul therefore distinguished between their graced situation as God's adopted children and that of Jesus as Son of God. In understanding the latter's "natural" divine sonship, Paul firstly spoke of God "sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful nature and to deal with sin" (Rom. 8:3). In a similar passage, Paul says that "when the fullness of time had come God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law" (Gal. 4:4). If one examines these three passages in some detail, it raises the question whether Paul thinks of an eternally pre-existent Son coming into the world from his Father in heaven to set humanity free from sin and death (Rom. 8:3, 32) and make it God's adopted children (Gal. 4:4–7). The answer will partly depend, first, on the way one interprets other Pauline passages which do not use the title "Son of God" (2 Cor. 8:9; Phil. 2:6–11). These latter passages present a pre-existent Christ taking the initiative, through his "generosity" in "becoming poor" for us and "assuming the form of a slave". The answer will, second, depend on whether one judges 1 Corinthians 8:6 and Colossians 1:16 to imply that as a pre-existent being the Son was active at creation. 1 Corinthians 8:6 without explicitly naming "the Son" as such, runs:

There is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist.

Calling God "the Father" clearly moves one toward talk of "the Son". In the case of Colossians 1:16, the whole hymn (Col. 1:15–20) does not give Jesus any title. However, he has just been referred to (Col. 1:13) as God's "beloved Son". Third, it should be observed that the language of "sending" (or, for that matter, "coming" with its stress on personal purpose (Mark 10:45 par.;Luke 12:49, 51 par.) by itself does not necessarily imply pre-existence. Otherwise one would have to ascribe pre-existence to John the Baptist, "a man sent from God", who "came to bear witness to the light" (John 1:6–8; cf. Matt. 11:10, 18 par.). In the Old Testament, angelic and human messengers, especially prophets, were "sent" by God, but one should add at once that the prophets sent by God were never called God's sons. It makes a difference that in the cited Pauline passages it was God's Son who was sent. Here being "sent" by God means more than merely receiving a divine commission and includes coming from a heavenly pre-existence and enjoying a divine origin. Fourth, in their context, the three Son of God passages here examined (Rom. 8:3, 32; Gal. 4:4) certainly do not focus on the Son's pre-existence, but on his being sent or given up to free human beings from sin and death, to make them God's adopted children, and to let them live (and pray) with the power of the indwelling Spirit. Nevertheless, the Apostle's soteriology presupposes here a Christology that includes divine pre-existence. It is precisely because Christ is the pre-existent Son who comes from the Father that he can turn human beings into God's adopted sons and daughters.

Gospel of John

In the Gospel of John, Jesus is the eternally pre-existent Son who was sent from heaven into the world by the Father (e.g., John 3:17; John 4:34; John 5:24–37) . He remains conscious of the divine pre-existence he enjoyed with the Father (John 8:23, John 8:38–42). He is one with the father (John 10:30; John 14:7) and loved by the Father (John 3:35; John 5:20; John 10:17; John 17:23–26). The Son has the divine power to give life and to judge (John 5:21–26; John 6:40; John 8:16; John 17:2). Through his death, resurrection, and ascension the Son is glorified by the Father (John 17:1–24), but it is not a glory that is thereby essentially enhanced. His glory not only existed from the time of the incarnation to reveal the Father (John 1:14), but also pre-existed the creation of the world (John 17:5-7-24). Where paul and the author of Hebrews picture Jesus almost as the elder brother or the first-born of God's new eschatological family (Rom 8:14–29; Heb 2:10–12), John insists even more on the clear qualitative difference between Jesus' sonship and that of others. Being God's "only Son" (John 1:14–1:18; John 3:16–3:18), he enjoys a truly unique and exclusive relationship with the Father.

At least four of these themes go back to the earthly Jesus himself. First, although one has no real evidence for holding that he was humanly aware of his eternal pre-existence as Son, his "Abba-consciousness" revealed an intimate loving relationship with the Father. The full Johannine development of the Father-Son relationship rests on an authentic basis in the Jesus-tradition (Mark 14:36; Matt. 11:25–26; 16:17; Luke 11:2). Second, Jesus not only thought of himself as God's Son, but also spoke of himself as sent by God. Once again, John develops the theme of the Son's mission, which is already present in sayings that at least partly go back to Jesus (Mark 9:37; Matt 15:24; Luke 10:16), especially in 12:6, where it is a question of the sending of a "beloved Son". Third, the Johannine theme of the Son with power to judge in the context of eternal life finds its original historical source in the sayings of Jesus about his power to dispose of things in the kingdom assigned to him by "my Father" (Luke 22:29–30) and about one's relationship to him deciding one's final destiny before God (Luke 12:8–9). Fourth, albeit less insistently, when inviting his audience to accept a new filial relationship with God, Jesus — as previously seen — distinguished his own relationship to God from theirs. The exclusive Johannine language of God's "only Son" has its real source in Jesus' preaching. All in all, Johannine theology fully deploys Jesus' divine sonship, but does so by building up what one already finds in the Synoptic Gospels and what, at least in part, derives from the earthly Jesus himself.

New Testament narrative

The Gospel of Mark begins by calling Jesus the Son of God and reaffirms the title twice when a voice from Heaven calls Jesus: "my Son" in Mark 1:11 and Mark 9:7.

In Matthew 14:33 after Jesus walks on water, the disciples tell Jesus: "You really are the Son of God!" In response to the question by Jesus, "But who do you say that I am?", Peter replied: "You are Christ, the Son of the living God". And Jesus answered him, "Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven" (Matthew 16:15–17). In Matthew 27:43, while Jesus hangs on the cross, the Jewish leaders mock him to ask God help, "for he said, I am the Son of God", referring to the claim of Jesus to be the Son of God. Matthew 27:54 and Mark 15:39 include the exclamation by the Roman commander: "He was surely the Son of God!" after the earthquake following the Crucifixion of Jesus.

In Luke 1:35, in the Annunciation, before the birth of Jesus, the angel tells Mary that her child "shall be called the Son of God". In Luke 4:41 (and Mark 3:11), when Jesus casts out demons, they fall down before him, and declare: "You are the Son of God."

In John 1:34 John the Baptist bears witness that Jesus is the Son of God and in John 11:27 Martha calls him the Messiah and the Son of God. In several passages in the Gospel of John assertions of Jesus being the Son of God are usually also assertions of his unity with the Father, as in John 14:7–9: "If you know me, then you will also know my Father" and "Whoever has seen me has seen the Father".

In John 19:7 the Jews cry out to Pontius Pilate "Crucify him" based on the charge that Jesus "made himself the Son of God." The charge that Jesus had declared himself "Son of God" was essential to the argument of the Jews from a religious perspective, as the charge that he had called himself King of the Jews was important to Pilate from a political perspective, for it meant possible rebellion against Rome.

Towards the end of his Gospel (in 20:31) John declares that the purpose for writing it was "that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God".

In Acts 9:20, after the Conversion of Paul the Apostle, and following his recovery, "straightway in the synagogues he proclaimed Jesus, that he is the Son of God."

Jesus' own assertions

When in Matthew 16:15–16 Apostle Peter states: "You are Christ, the Son of the living God" Jesus not only accepts the titles, but calls Peter "blessed" and declares the profession a divine revelation by stating: "flesh and blood did not reveal it to you, but my Father who is in Heaven." By emphatically endorsing both titles as divine revelation, Jesus unequivocally declares himself to be both Christ and the Son of God in Matthew 16:15–16. The reference to his Father in Heaven is itself a separate assertion of sonship within the same statement.

In the Sanhedrin trial of Jesus in Mark 14:61 when the high priest asked Jesus: "Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?" Jesus responded "I am". Jesus' claim here was emphatic enough to make the high priest tear his robe.

In the new Testament Jesus uses the term "my Father" as a direct and unequivocal assertion of his sonship, and a unique relationship with the Father beyond any attribution of titles by others:

- In Matthew 11:27 Jesus claims a direct relationship to God the Father: "No one knows the Son except the Father and no one knows the Father except the Son", asserting the mutual knowledge he has with the Father.

- In John 5:23 he claims that the Son and the Father receive the same type of honor, stating: "so that all may honor the Son, just as they honor the Father".

- In John 5:26 he claims to possess life as the Father does: "Just as the Father has life in himself, so also he gave to his Son the possession of life in himself".

In a number of other episodes Jesus claims sonship by referring to the Father, e.g. in Luke 2:49 when he is found in the temple a young Jesus calls the temple "my Father's house", just as he does later in John 2:16 in the Cleansing of the Temple episode. In Matthew 1:11 and Luke 3:22 Jesus allows himself to be called the Son of God by the voice from above, not objecting to the title.

References to "my Father" by Jesus in the New Testament are distinguished in that he never includes other individuals in them and only refers to his Father, however when addressing the disciples he uses your Father, excluding himself from the reference.

0 comments:

Post a Comment